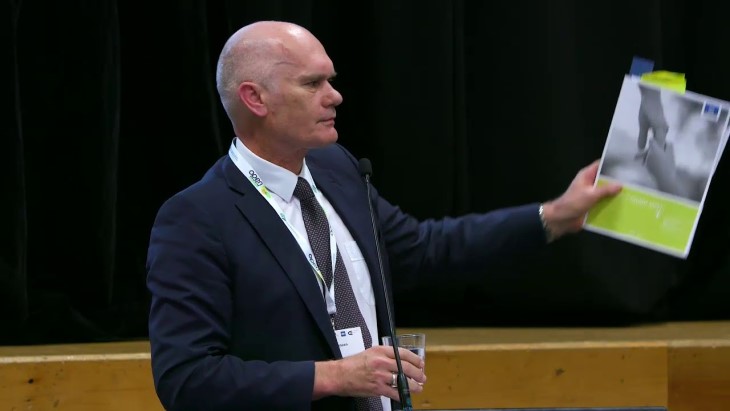

Dr Peter Jansen: The importance of culturally appropriate care

Passionate about achieving equity of health outcomes, Dr Peter Jansen is an expert on cultural competency. He shares his story with us, explaining why receiving culturally appropriate care is so important.

I was born in Hamilton and my iwi connections are Ngāti Hinerangi, from the area surrounding the Matamata township.

I went to medical school in Otago and then started practicing as a GP in Whangamatā, a lovely surfing town in the Coromandel Peninsula.

A number of my whānau live around there so that was awesome for my kids growing up. I’ve never been on a surfboard in my life but they got heavily involved in the local surf lifesaving club.

My son was actually involved in the rescue of one of my aunties and I think helping to save someone’s life like that is part of what inspired him to go to medical school. Observing a rural general practice up close must also have had an impact on him.

My brother, his oldest son and one of my nieces also went to medical school, so there’s now five of us Doctor Jansen’s around.

Improving quality of care for all

I worked in primary care in Whangamatā for seven years and then shifted up to Papakura in South Auckland.

That was at a time when organisations like Pro Care were starting up – they’re committed to creating better, more equitable health outcomes for New Zealanders.

I was on the inaugural Pro Care board and they said to me, ‘Well, you keep banging on about quality of care, you can be the chair of the quality committee. And, by the way, because you keep talking about the needs of Māori patients, you can also be in charge of improving Māori health’.

Now, those two things in my mind are always joined up. If you want high quality care for all patients, then you certainly want it for Māori. And if you can provide the highest quality care for Māori, then you’ll probably be providing it for all patients – that’s just logic.

I was also working within the Māori Medical Practitioners Association (Te ORA) to look at training opportunities for Māori doctors and support them in their careers. It was all part of this idea of providing high quality care for all patients – we know that you and I, and everybody else is going to be much happier when they have a provider who’s in tune with their own culture.

That was really successful and we had a number of graduates who went on to do really good things in the New Zealand health system.

A new perspective on life

But then I got crook – I got head and neck cancer, this was about 20 years ago now.

At the end of a long treatment period, which was pretty intense with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, I was back to work.

That made me look at life a bit differently and ask myself, what do I really want to do?

So I teamed up with my brother Rawiri, who’s now the chief medical officer at Te Aka Whai Ora (Māori Health Authority), and my great friend Rees Tapsell, who runs forensic psychiatric services in the middle of the North Island, to start a little consultancy company called Mauri Ora.

Our objective was to improve Māori health equity through training the Aotearoa health workforce.

Landscape changes with passing of Act

A seminal event then took place with the passing of the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act in 2003, which gave the health professions a common direction of travel to steer us towards better patient care.

A section of that Act talks about the functions of the authorities and one of those was to make sure that standards of cultural competence were observed by all practitioners.

But a lot of the organisations said, ‘Gosh, how do we do that?’ So we worked with a number of them to help define what that was for them.

Irihapeti Ramsden, who worked so hard to improve health outcomes for Māori people, made the point that there’s an even better concept – it’s called cultural safety. That’s about how the perception of whether your care meets cultural needs is up to the receiver of the service and their whānau to determine.

That’s the perspective ACC staff and service providers need to take to make changes for good.

This is the essential difference between cultural competence and cultural safety. We can all be educated and trained in how to do something but whether that meets the needs of the patient can only be judged by that patient and their family.

Cultural competency vs cultural safety

Cultural safety isn’t just about doing one specific thing to meet the needs of patients – it’s about understanding your culture and how that impacts on your approach to people.

For example, if you think about when you go to the doctor and you get shown to the consultation room, sometimes the doctor will lead you in, but other times they’ll stand back and wave you in. That will depend on how they feel about you, and it may come from their cultural background.

A typical Māori doctor’s response might be to stand in the room and welcome the patient in, to welcome you into their space. That’s what would have happened the last time you went to the marae, the home folks welcomed you in and there was an appropriate exchange of pleasantries.

Now you might think we could just teach all that but that’s not the end of it. You need to think about it from the patient’s perspective – how did they experience that, and what was their preference?

So the next step is to think about how you would respectfully ask the patient what their preference is and explain what you’re going to do in a way that is understandable, so you can have an agreement for future interactions.

Fronting up to your biases

The key is not so much about running off and finding out about other cultures. It’s about finding out about yourself – where are my blind spots, where are my weaknesses that I need to work on in terms of understanding how I interact with other people.

In addition, we all have biases so it’s useful to find out what those are. For example, you could go and do an implicit biases test in relation to ethnicity, gender or age – they’re freely available online.

I’ve done them and found out that, because I’ve been brought up in a male-dominated culture, I do have a streak of misogyny in me. I’m now aware I need to self-correct to account for my biases, so the people I interact with get a package of care that’s more acceptable to them.

So that’s cultural safety, it’s more about me and my interactions with others, while cultural competency is more about the knowledge required to learn about other cultures and typical cultural preferences.

A matter of life and death

I’ll give you an example of how important cultural safety can be. About 20 years ago, there was a case published by the Health and Disability Commissioner which involved a man of Pacific origin.

He was in the emergency department of a major hospital after being struck on the head. He was being assessed and was with his wife.

The staff thought he was speaking a Pacific language but his wife was thinking, ‘He’s speaking gibberish, why aren’t they doing anything?’

The Pacific family was being polite and allowing the clinical team to do their thing without interrupting them. And the clinical team thought they were doing the right thing because they figured the guy was talking to his wife in a language they didn’t know.

But nobody thought to check, is what he’s saying making sense to the people around him? Sadly, that gentleman ended up passing away.

So it can literally be a case of life or death sometimes.

Setting a goal for equity

We’ve known for more than 20 years that there is differential access to ACC services for Māori when compared to non-Māori, non-Pacific people. Some work has been done in addressing this inequity but we do need to go up a level.

I’m optimistic but I’m also a realist. I’d like to see equitable outcomes for Māori but I think we need to set a time to aim for as well as the target – the date I have in mind is 2040 and the goal is that Māori receive services equitably in accord with the general rules of cultural safety.

The date is of course the bicentennial of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Surely, we’d be able to get to that date and be able to say we’ve achieved equity, both in access and outcomes for Māori in health and disability services and in support from ACC after injury.

You wouldn’t want to be standing on the dais in 2040 going, ‘Gee, we’ve not lived up to the dream’.

So I think ‘Let’s set a date for equity’ has got to be the mantra. We’ve got to do much better than we’ve done because we can’t allow a situation to continue where a large proportion of our country’s people are getting less, for no good reason.

We know Māori go as often to their GP and pick up their medicines in the same proportion as they’re prescribed as others. But we’re not getting the same rate of referral to secondary care or to ACC and not the same outcomes as other New Zealanders.

So we have to do something about that, starting now.

Some of the kaimahi Māori who help ACC embed Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles into our mahi.

If you're a health provider and would like to find out more, or watch a recent webinar from Dr Peter Jansen on Cultural Competency Guidance, please visit the 'Cultural safety and competencies' section of our website.